|

M. FORD CREECH ANTIQUES & FINE ARTS

WHAT'S SO SPECIAL ABOUT THE 18TH CENTURY?

This is a question that is frequently put to me - as I have a particular passion for the time period.

Below is my answer - at least part of it.

|

|

|

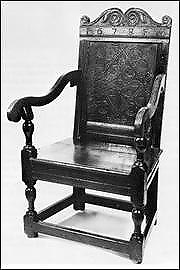

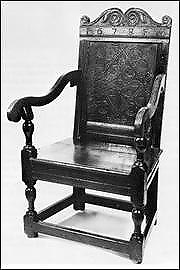

A George II Carved Walnut Open Armchair c1720 / A Charles II Carved Oak Wainscot Chair, 1678 |

| |

The 18th century and the short periods on either side, roughly from 1680-1830, represent "The Golden Age" in the fields of furniture and decorative arts. That time period stands as one of the pinnacles of mankind's creations. Design in Europe, England and America, particularly in furniture, seemed suddenly to awaken from the post-medieval utilitarian forms, moving from joined and architecturally based furniture of the mid 1600's, to the grace and elegance of Queen Anne and Regence in a mere 50 years.

For instance, chairs were not really known for the average person until about 1650. The head of a household - or a king or queen - may have had a wonderful armchair - some known as wainscot chairs. (See the above Wainscot chair, dated 1678). However, the rest of the world sat on stools or benches. The first chairs for the populace were introduced in the mid-17th century and called backstools, as they simply had a back placed upon a "joined" stool.* By joined, I mean put together without the use of nails by what we know as mortise and tenon joints, and pegs - which, by the way, were indeed square pegs urged into round holes. Even chests were put together without the use of nails until about 1660. Within but a very few years, the elegance of sculpturally curved lines and comfortable grace came into being. One look can convince you of the overwhelming transformation that took place in those very few years. (Again see the c1730 British open armchair - just a few years beyond the Wainscott beside it). This was in part due - once more - to the imports from China, as the spoon back of the Ming chairs, and caning, as well as the ball and claw, which is the actually dragon chasing the flaming pearl

(known as the "heart of Buddha").

18th century forms of England and Europe embody a purity of line and perfection of proportion not equaled before or since. The era saw four new design styles, or "periods". Each "period" had exacting disciplines and characteristics to be followed for the varied products, i.e. silver, ceramics, furniture, and the various associated decorative items.

A shortened stylistic chart is at right.

Each "period" rapidly followed another, as a reaction to, or improvement upon the previous style, reflecting politics, world commerce, and changing social structures. And very great artisans, such as Huguenot silversmiths Pierre Platel and Paul de Lamarie, well known cabinetmakers Thomas Chippendale, and later George Hepplewhite and Thomas Sheraton in England, and Andre-Charles Boulle, Jean-Francois Oeben, and Jean-Henri Riesener in France, are among just a few of the innovators setting the standards for those disciplines. |

|

THE STYLISTIC PERIODS :

Early Baroque, massive, with much Dutch influence (c1680-1700):

Symmetry and self contained design; c-scrolls, with curves and counter-curves introduced; furniture used oak, walnut and exotic woods, as well as mortise and tenon joints, and dovetails.

Late Baroque, sculptural, self-contained and symmetrical, with strong curves and counter curves, yet all with more delicacy (c1700-1730):

The same principles as in Early Baroque still remain, but with much more grace and elegance. The curve became more prominent, with the introduction "cabriole" legs and ball and claw feet on furniture, as well as silver and ceramics; the shell motif became quite important; walnut was the wood of choice.

Rococo, exhibiting great French influence over the world, and ornamentation with sinuous curves and asymmetry (c1730-1770):

No longer symmetrical, but extending beyond itself, as is "ears" on "Chippendale" chairs; much carving and piercing of surfaces; delicacy and fragility as opposed to the former solidity; mahogany introduced.

Neoclassical, with its restraint and reference to Greco-Roman and later Egyptian ornament and style (c1770-1820):

Geometric and again symmetrical; lightness of form; rational with, no waste or frivolity; inlay and thin veneers became quite important.

(In America and other colonies, the "periods" ran somewhat behind, just as even today, New York and Paris often enter a fashion before the rest of the world.

30 years is often a suggested lag time).

|

|

|

|

| |

Even as phenomenal was the technical evolution that occurred.

Each stylistic change involved developing - or discovering - new methods to produce their wares.

The story of ceramics alone is one of trial, error, secrecy, greed, and royal power.

In the case of Meissen, Augustus the Strong of Saxony threatened the young alchemist Bottger in 1703 with his life

unless he found the secret to the Chinese porcelain** (kaolin - a hard china stone that would survive high temperatures).

The development of Sevres was the passion Madame Pompadour, the mistress of Louis XV.

When kaolin was discovered in France in 1753, Louis declared Sevres a Royal Manufactory,

and forbade every other French company from using anything but underglaze blue on their ceramics.

England, meanwhile, simply wanted a cup of tea in something that the hot water would not break,

developing their first successful "soft paste", or "artificial porcelain", in the 1740's.

They used everything from ground glass and soapstone, to boiled ox bone knee,

the latter being later used in the formulation of bone china, once more - in the late 18th century.

The first Worcester (making the finest teawares) was produced in 1751, the company still existing today as the Royal Worcester Manufactory.

Much of the 17th century silver was quite thin and stamped, thus not a great deal survives.

However the skill, particularly of the Huguenot silversmiths throughout 18th century,

has left us a vast heritage, upon which most of our current styles are based.

In the 1600's, the average person ate with a bone, pewter, wooden, or brass spoon.

Until the early 1700's, the wealthy only had a silver spoon - and probably only one -

which was carried about on the person when travelling.

Cutlery - in the form of a sharp carving knife and a fork that looks like a current day carving fork-

might be carried in a sleeve about the waist.

In about 1700, sets of silver spoons began to appear, as well as 3-tined dinner forks -

the three tines representing the thumb and two fingers that had been used for non-liquid food for centuries.

Flatware as we know it today appeared in services about 1760, first as the famous Old English pattern.

Candlesticks in 1700 were only 6" or 7" tall.

By 1740, they were about 9'' tall, with the first detachable bobeche (a drip-pan to catch the dripping wax).

By 1770, the candlesticks had risen to about 12" in height, the reeded Corinthian column being a familiar style,

and the 3-branched candelabra first became popular.

Silver tea services were collected as individual pieces until 1780, when the first sets were introduced.

The designs we now use for salts, condiment dispensers, goblets, serving dishes, tureens and platters of all kinds were also innovations of that time,

all still used as a model for many contemporary wares.

In furniture, new techniques,

such as dovetails, veneers, intricate carving on hard woods, and strong glues were but a few of the developments.

Walnut is quite a hard wood and very difficult to carve; so the importation of mahogany from the New World in the late 1720's

gave birth to the sinuous carved and pierced rococo ornamentation.

The introduction of the circular saw in 1780 meant that furniture could be made with a new lightness and elegance,

thin inlays and spare lines. Among the furniture resulting from the circular saw are the popular 2-4 pedestal dining table,

and the sideboard, giving birth to the dining room as we know it.

Prior to about 1780, there was no specified dining room.

Dining tables consisted of heavy refectory tables in a great hall, or simple gate-leg and drop leaf tables, dragged to and from the wall for dinner or tea.

In 1750, Lady Pembroke ordered a small drop leaf supper table,

to be built with a lower shelf, doors, and a wire covering - to keep the rats out of the food.

That was the first "Pembroke table" we now use at the end of our sofas.

These are but a very few of the familiar items we take for granted every day, first conceived and produced in the 18th century,

which first had to produce the technology and craftsmanship, as well as design.

Perhaps it could be said that the speed and quality of the advancements taking place at that time can be compared

to the 20th century advances in transportation, technology and communication.

Most 18th century pieces were hand crafted for the wealthier upper classes, and many approached as a piece of art.

The material (as imported rare timbers, or fine silver) might be worth far more than the craftsman's time -

so that perfection was the goal.

By 1750, the stage for Industrial Revolution was set,

with the introduction of the steam engine in 1775 and, as stated the circular saw in 1780.

By 1800, a large middle class had developed, and with money to spend.

They, too, desired these wares that had been made for the wealthy in the previous century.

The quickly resulting production for the masses, (German Biedermeier actually reflects that purpose in its name:

bieder - made for, meier - a common name in Germany, or, meaning "for the average man"),

and the 1830 introduction of the dowel for furniture construction, changed craftsmanship and proportions dramatically.

Further, the first World's Fair took place in London in 1851 at the Crystal Palace,

with the entire Western world displaying beneath one roof.

What followed were revivals of the previous styles (i.e. Rococo Revival, Classical Revival, etc.),

but with combination of styles, and changes in construction, line and proportion, often greatly compromising the previous purity of design.

Finishing techniques changed the outward appearances of furniture.

And transfer decoration on ceramics, developed by Worcester in 1756, replaced much of the 18th century hand painting of ceramics.

This scene would dominate the 19th century European and American design

from approximately the beginning of Queen Victoria's of England in 1837.

And although many craftsmen retained high standards of production,

mass production overtook others, and the quality and intent for perfection was lost.

That precept of profit over quality is still too much with us today.

Although beauty and purity are made throughout history,

the better to best pieces from the 18th century continue to hold an unequalled position.

Despite all trends or "reflective periods", they will continue to be prized and appreciate strongly in value.

An added dividend :

the beauty and historic legacy they bring is seen, touched, is measured and treasured daily.

That - is priceless.

Millicent Creech

M. Ford Antiques & Fine Art, Memphis, TN USA

*18th century stools are comparatively rare and expensive, as stools were associated with the 17th century.

No one wanted to sit on them. It was not until the early 19th century that they regained popularity.

A fine pair of early to mid-18th century stools can bring as much as $50,000.00 at auction.

**Chinese porcelain had been imported into Europe since the late 1400's, and was considered more valuable than gold

|

|

PLEASE INQUIRE

We welcome and encourage

all inquiries regarding our stock. We will make every attempt to answer any questions you might

have.

For

information, call (901) 761-1163 or (901) 827-4668, or

Email : mfcreech@bellsouth.net or mfordcreech@gmail.com

American Express, Mastercard, Visa and Discover accepted

Become a fan on Facebook Become a fan on Facebook

M. Ford Creech Antiques & Fine Arts / 581

South Perkins Road / Memphis,

TN 38117 / USA /

Wed.-Sat. 11-6, or by appointment

|