|

M. FORD CREECH ANTIQUES & FINE ARTS

The Evolution in Iconography from the Mother & Child to the Madonna & Child in Fine Art (from c 37,000 BCE - the 20th century)

As far back as the Paleolithic period, humans have created icons in the image of women. Fertility, sexuality & life all realized in these small hand carved figurines - their symbolism transcending time to grace our eyes with equal power as when created.

(left) Venus of Hohle Fels, c 37,800 BCE, mammoth ivory, Germany (right) Venus of Dolni Vestonice, c 29,000 - 25,000 BCE, ceramic, Czech Republic

In fact, the female form has remained integral to the majority of cultures throughout history. In particular, female goddesses (often depicted as mother and child) were especially fundamental to Egypt and the Mediterranean.

"For the ancient Egyptians the image of the goddess Isis suckling her son Horus was a powerful symbol of rebirth that was carried into the Ptolemaic period and later transferred to Rome, where the cult of the goddess was established."

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

(left) Statuette of Isis & Horus, 332-30 BCE, Faience, Egypt (right) Woman & Child, 3rd Century CE, Catacombs of Priscilla, Rome (Woman holding child on her knee)

Shown above is one representation of an Egyptian female icon - of Isis and Horus (in faience or glazed pottery), characterized by the gesture of offering a breast for feeding - called the lactans-type.

In Egypt, lactans icons symbolized life giving nourishment & divinity. These icons of Isis lactans can be found in the Mediterranean from as early as 700 BCE until the 4th century CE

(left) Limestone statuette of Isis lactans, 4th century CE, from Antinoe, Egypt (Isis holds her breast with her right hand while Horus lies across her knee) (right) Virgin Enthroned Between Saints & Angels, late 6th century, encaustic on wood, Monastery of St. Catherine, Egypt ;

In 313 CE, the Edict of Milan was decreed. It solidified the agreement from Rome to treat Christians benevolently within the Empire. Christian theologians, faced with a growing religion and a new tolerance, had to determine how the religion would be consumed going forward. This meant strict visual parameters for artwork and establishing a hierarchy of the saints in order to make the doctrine more digestable to the public.

It is of interest to note that Rome had used images of the mother and child for political propaganda - often representing hope, safety, and security... all characteristics that would be embodied by the Virgin in Christianity. The influence Roman art had on their Christian neighbors is evident. In the encaustic icon (above left), Roman modeling is used on the face to imply soft round form.

In 431, at the Council of Ephesus, Mary, more specifically her role in Christianity, was at the heart of an important debate - whether Mary had given birth to Jesus (the man) or to God (the Father).

(above) Maria lactans at the Monastery of Apa Jeremiah at Saqqara, 7th century CE, Coptic Museum, Cairo

The clash was eventually settled and Mary was deemed "Theotokos" meaning "the one who bore God", affirming the full divinity of the Christ-child and Mary's role as the intercessor between Christ and man - she is the vessel.

(above) Frescoes of Maria lactans in the church of Anba Bishay, Red Monastery, 7th - 8th century CE

Early Byzantine religious artworks confirm this new identity. As seen above, the Maria lactans frescoes are formal and used to show the position of Mary as the keeper of Christ between people and God; Mary & Christ are only connected by their proximity to each other, not by an obvious maternal or emotional bond.

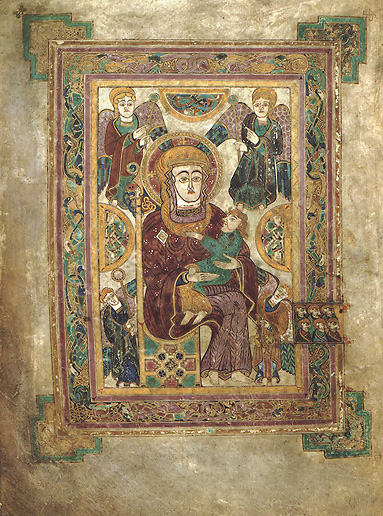

(above) Madonna & Child from the Book of Kells, Folio 7v, Late 8th century, Scotland

During the Iconoclasm (both in 726 - 787 and again in 814-842), Byzantine theologians were again split on how to define Mary. It was decided that she was mother not only to Christ but to all of the faithful. No longer just "the one who bore God", "Theotokos", she was now "Meter Theou", "Mother of God" - shown, now, with affection & maternal emotions towards Christ.

With the reinstitution of iconography, artists were tasked to develop Mary's maternal, earthly side.

(above) The Virgin & Child (Theotokos) Mosaic, 867 CE, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, Turkey

Unlike the Frescoes of Maria lactans in the church of Anba Bishay or the encaustic Virgin Enthroned Between Saints & Angels, the Virgin & Child (Theotokos) Mosaic in the apse of the Hagia Sophia (above) and the Madonna & Child from the Book of Kells (above), show mother and child alone - a singular unit, without setting or accompanying figures. The "Madonna & Child" mosaic was the first icon to be put on the walls in the Hagia Sophia after the Iconoclasm ended - (a strong message from the church) solidifying the significance of her relationship with Christ.

Even with a new personality, it was not until the Romanesque period (11th century - 12th century) that artists began to depict the Madonna with obvious emotions - even then, only for small personal devotional figures like the two figurines below. In the "Morgan Madonna", her eyes show a sad, knowing expression - foreshadowing the future for her Christ-child. Both hands are even wrapped around the child, as if to protect him.

(left) Virgin from Ger, second half of the 12th century, wood, tempera and stucco, Spain (right) Morgan Madonna, c1175-1200, walnut with paint, Auvergne, France

In the Gothic Period, The "Madonna of Humility" replaced the emotional, yet stiff persona of the Middle Ages. Artists, like Cimabue and Duccio, continued to push the formal conventions, bringing life and a sense of relation to their subjects. Mary was now approachable - a mother - intimate and loving

(left) Shrine of the Virgin, c 1300, German (right) Lorenzetti, Madonna & Child, c1325, tempera on gold panel

And so it went, portrayals of the Virgin and Child from the late 12th century, forward grew increasingly tender - seeking to inspire piety through beauty, tenderness, and grace. As seen above in the closed version of the Shrine of the Virgin, in which Mary gazes down at the Christ child as he nurses. Lorenzetti's Madonna (above) gently presses her cheek to her child.

(left) Giovanni dal Ponte, Madonna & Child with Angels, c 1410, tempera and tooled gold leaf on panel, Italy (right) follower of Robert Campin, Virgin & Child before a Firescreen, c 1440, oil with egg on tempera on oak, Netherlands

The evolution of Madonna and child went on to take many forms. The "Madonna of Mercy" became popular in the 15th century - as seen in dal Ponte's Madonna & Child with Angel (above), the angels extend her mantel to protect the pious...

(above) Botticelli, The Virgin & Child (Madonna of the Book), 1480, tempera on wood, Italy

...to the equally as popular portrayal of a humble and domestic Madonna. Botticelli's Madonna of the Book, overflows with symbolism - the cherries in the bowl a symbol of the blood of Christ, the plums to the love between Mother and Child, the figs to the Salvation or the Resurrection.

(left) Workshop of Luini, The Virgin & Child, early 16th century, oil on wood, Italy (right) Raphael Santi, Bridgewater Madonna, c 1507, Italy

In the 16th century, the domestic, approachable Mary remained popular. With quiet reverence, The Virgin & Child from the workshop of Luini (above), invites the viewer into an intimate moment between mother and son. Mary looks over to her son with the curiosity of a new mother, wondering what he will do next. The earthy tones emphasize the humanity in the pair, the only acknowledgment of his divinity and her sainthood in the glint of gold around their heads.

(above) Hans Holbein the Younger, Virgin of Mercy, 1526

Holbein revisited the Madonna of Mercy trope with his own aptly titled, Madonna of Mercy (above), shown with her mantle extended out to cover and protect the pious.

Simon Vouet, Madonna & Child, 1633, oil on canvas, France

The 17th century highlighted "immacolata", the immaculate conception, a brief period in art where Mary was often not seen with the child, but as a young girl descending from heaven. The above example by Vouet, an exquisite exception. Breaking from all tradition, Vouet paints a mother and her child, enraptured in themselves, playful and loving. Mary only recognizable by her red and blue robes.

(above) Giuseppe Maria Crespi, The Madonna & Child, 1665 - 1747, Italy

One of the other few paintings of the pair is Crespi's The Madonna & Child (above), which, like Vouet's, also shows a doting and soft Madonna & Child. Her earthy green mantle shading her son from his eventual fate. The tenderness in her face along with the quiet intimacy of the moment reflects the desire of the people in the 17th and 18th century to see themselves in Mary.

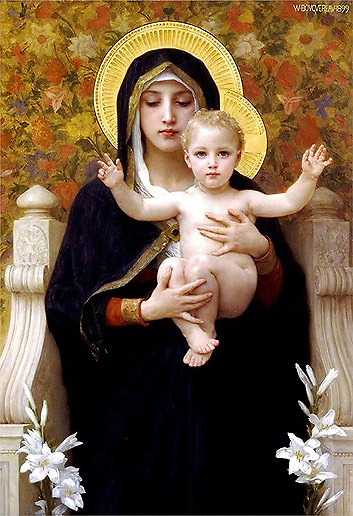

(above) Bouguereau, The Madonna of the Lillies, 1899, oil on Canvas, France

The patronage and popularity of religious art declined after the 17th century. Singular artists in the 18th and 19th century would touch on the topic, using a style popular in the Renaissance, as did Bouguereau with his Madonna of the Lilies (above).

(above) Mary Cassatt, Mother & Child, c 1900, pastel on paper, American

In the 20th century, Mary Cassatt's work brought fresh life to the Madonna & child. Interestingly, the response to her mother and child was polar opposite to the most famous Mother and Child on earth, the Madonna and Child. Her paintings (an example above) were thought at the time to be unremarkable domestic scenes painted by a woman, but would later receive the acclaim they so deserve. Cassatt's work involves itself in the long conversation humanity has with mother and child iconography - each individual takes what they need from it. Do you need tender eyes of reassurance? Look to the Madonna's of Cassatt or Crespi. Maybe you want to feel small in front of the endless and all encompassing nature of God? Look to the mosaics in the Hagia Sophia or gaze on the statues of Isis Lactans and Horus.

Each one waiting to engage us in conversation about the timeless reward of life and love and the strength of human connection.

Compiled with love and curiosity by Anna Bearman for M. Ford Creech Antiques & Fine Arts

Works Cited

1. Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Madonna." Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 19 June 2015, www.britannica.com/topic/Madonna-religious-art.

2. Higgins, Sabrina. (2012). Divine Mothers: The Influence of Isis on the Virgin Mary in Egyptian Lactans- Iconography. Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies. 3-4. 71-90.

3. Kalavrezou, Ioli. "Images of the Mother: When the Virgin Mary Became 'Meter Theou.'" Dumbarton Oaks Papers, vol. 44, 1990, pp. 165-172. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1291625.

4. Muther, R. (1907). The History of Painting: From the Fourth to the Early Nineteenth Century (Vol. 1). G.P. Putnam's Sons.

5. "Statuette of Isis and Horus." Metmuseum.org, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/55.121.5/.

We welcome and encourage all inquiries regarding our stock. We will make every attempt to answer any questions you might have.

For information, call (901) 761-1163 or (901) 827-4668, or Email : mfcreech@bellsouth.net or mfordcreech@gmail.com American Express, Mastercard, Visa and Discover accepted

M. Ford Creech Antiques & Fine Arts / 581 South Perkins Road / Memphis, TN 38117 / USA / Wed.-Sat. 11-6, or by appointment

|

Child_Trinity_College_Ireland_index_200w.jpg)