Early Chinese porcelain in Europe is a legend in its own right :

mysterious in origin, in manufacture and in appearance.

Europeans had no such substance - only heavy soft and easily broken pottery.

The "early" white, and blue-and-white wares became the gift of royalty, and the mark of status.

Many Europeans honored it further by applying gilt metal or silver mounts.

By far, the most prolific at these mounts were the Dutch.

In the early 1600s, the Dutch achieved domination of the seas,

together with the European trade in 'chinawares' (another name for the ceramics).

The Dutch dominance was brought about primarily by their great desire for Chinese porcelain.

However this story does not begin that way.

PORCELAIN : Its ALLURE & POWER

In the1480s, the first few pieces of blue-and-white Chinese porcelain began trickling into Europe.

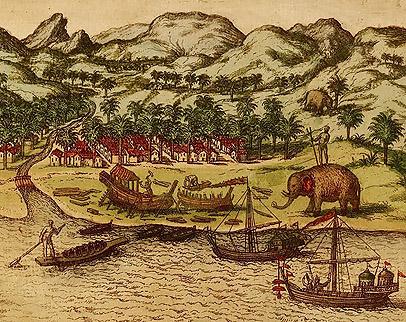

In 1497, Portugal’s rather enthusiastic King Manuel I instructed Vasco da Gama,

on departure of his famous first exploratory voyage to "India" (above left),

to bring back "porcellanas".... along with some spices and Christians ....

(It is thought that the above right ewer was among early wares ordered by Manuel I,

the body with symbolism from a European engraving, or a "Book of Hours").

Manuel I subsequently began the practice of presenting the coveted

blue-and-white porcelains to the royal families of Europe.

This included Holland.

From c1500-1600, the Portuguese imported vast amounts of Chinese porcelain.

These hard shiny ceramics were an exotic and wondrous curiosity to all.

The wares had been transported in below-water holds from far-away mysterious lands.

Its material and method of manufacture were barely understood.

The wares were even imbued with various superstitions.

And its value was equated with gold.

It was much desired by all - in particular - Holland,

who joined the maritime quest, making extremely lengthy & expensive journeys to the East Indies.

However, Portugal held a complete monopoly on trade with the East ---

power, ships and money.

The Dutch could reach the East, but could not produce enough funds to buy the ceramics.

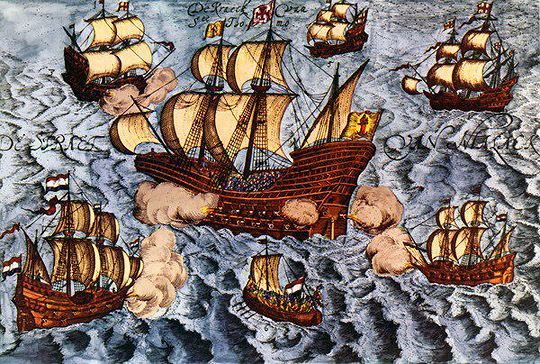

However, they soon learned the Portuguese shipping routes, and near Singapore, in 1603,

captured the 1500-ton Portuguese "carrack" Santa Catarina (the battle below) -

- and the 200,000+ pieces of Ming Chinese porcelain aboard!

Ming blue-and-white porcelain (made for export to the West) is to this day

referred to as "kraakporselein", after the captured Portuguese "carrack"(sailing vessel).

This allure of

Chinese ceramics had, in short,

directed the

presiding maritime powers of 15-17th century Europe.

From the 1603 Santa Catarina capture and throughout the 17th century, under the auspices of the VOC

(Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compangnie), the Dutch replaced the Portuguese

in worldwide maritime dominance, building a vast trading network

moving goods - and porcelains - among Europe, Asia, and the Americas.

The "METAL MOUNTS"

:

As the earliest (1500s)

porcelains were extremely costly rarities,

many of the very few

pieces available were provided with precious metal mounts.

During the 1600s, the

VOC provided Holland with an abundance of Oriental porcelain -

both Chinese and, after

c1620, Japanese.

However, few mounts seem

to exist from that period.

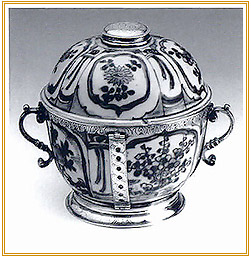

This covered Wan Li

bowl, c1618, is the earliest known piece of Chinese porcelain

provided with Dutch

silver mounts.

(above, Fries Museum,

Leeuwarden)

These mounts consist of

four simple clamps with interlaced openwork

joining the footrim and

the upper sections together,

both the mounts and

ceramic complimenting each other.

Alternately French

mounts were much more elaborate, and could possibly upstage the

precious ceramic.

English metal mounts

were generally heavier - but simpler.

Early 17th century Dutch

still life paintings frequently depicted - with exaction -

these Chinese

blue-and-white - both with and without metal mounts.

Note the small

blue-and-white metal-mounted "mustard jar" in this Pieter Claesz

still life, 1643.

It was not until the

18th century that the Dutch began the delightful and extensive use

of silver mounts.

These applied mounts

could be plain or engraved -

(as free standing

flower-heads or animals).

The ceramics chosen for

mounts were generally "fitted" for aesthetic reasons -

although for functional

improvements as well.

(Late 17c Kangxi Teapot

with Collar & Chain / Personal Collection)

To the European eye,

metal mounts visually and monetarily enhanced the value of porcelain

.

Further, a mount could

transform a simple decorative jar into something more useful.

In order to be fitted,

sometimes the porcelain itself sometimes had to be altered -

a swelling on a neck

filed to accept the silver collar, etc.

To the European, that

alteration was not considered a detriment to the piece.

As well, pieces

damaged in the long voyage often received a silver covering

or enforcement of the mend.

Popular also was the

joining of a jar or teapot cover and vessel by a collar and chain or

hinge.

The porcelain most

selected for silver mounts is blue-and-white,

dating primarily from

the 1662-1722 Kangxi period (considered to be the height of blue and

white)

and through the

Yonzgheng, and early Qianlong periods (to c1740).

The mounting of early

blue-and-white wares remained popular to the mid-19th century,

the majority of the

Dutch silver mounts offered today being of 19th century manufacture.

The VISUAL APPEAL

:

There is something

sensual and extremely appealing about

the combination of

silver with blue-and-white porcelain -

far moreso than on the

colored wares.

Each substance seems to

enhance the other without competing - making the eye quietly

"dance".

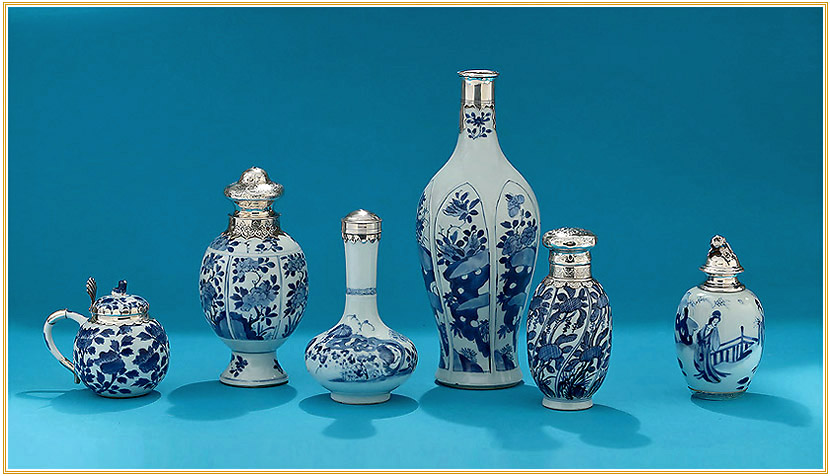

We present the following

silver-mounted Kangxi examples

for sale, as well as

your visual pleasure.

It is a porcelain

category that I very much like to look at, to handle -- and to own.

It also boggles the

imagination that something so gentle as a jar

could direct the

dominance of nations -

even without silver

mounts!

|

|

Kangxi Silver-Mounted Mustard Pot, c1700

The domed cover with a seated fu dog finial,

the body painted with chrysanthemums & birds;

the silver mounts with thumb lift &19c Dutch mark

Fu (or foo) dogs are Chinese guardian symbols,

said to protect the home from malicious spirits |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kangxi Silver-Mounted Bottle Vase, c1700

The mounts, European, 18th / early 19th century;

The slender neck mounted with a silver collar and

screw-on top; body with mushrooms & blue hollow

rocks; verso with Kangxi artemesia leaf mark

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Kangxi Silver-Mounted Moulded Tea Caddy

The Porcelain, c1700, the Mounts Dutch, 1858

Wrythen moulded body with panels of flowerheads,

the neck & cover with well engraved silver mounts;

fully marked

|

|

|

|

A FOOTNOTE :

Actually a bit of credit for all this is due to the ferocious Genghis Khan.

By 1279, Khan and his descendents had expanded the Mongol empire

westward to include Persia and parts of Europe.

At this time, China's "sacred color" was "white".

As well, the Chinese cobalt (mineral for blue) tended to turn black.

Thus they had not put much emphasis upon cobalt for porcelain decoration.

At the western end of the empire, Persia's "sacred color" was "bright blue".

And Persia possessed a cobalt ore making just such a hue -

but could fire only soft clay potteries..

About 1330, Persia sent to China a quantity of bright-blue firing cobalt ores

(along with a few Egyptian metalwares for shapes),

requesting that China produce for them (Persia) :

blue-and-white porcelains!

Thus it is Persian cobalt on Egyptian shapes that instigated

the legend of what all of Europe was soon to covet :

Ming (and Kangxi,1662-1722,) blue-and-white wares,

that traveled by sea (some few by road)

westward to Persia and India - thence in the 1400s into Europe -

where our particular story began.

Some of the finest examples of Ming blue-and-white still resides in the Topkapi Palace Museum, Istanbul.

And some of the finest silver-mounted blue-and-white still seems to live in Holland!

|